|

My

Model 75 Troy Radio

The Troy

Radio and Television Company was a relatively small radio manufacturing

enterprise once located at 1144 South Olive

Street in Los Angeles, California at a location that is now the parking

lot for the AT&T business center. The Troy Radio Company was

one

of hundreds of small

American radio manufacturers that successfully tapped into the thriving

market for radios during the era of The Great Depression. They

were not a major brand and I think it is

unlikely that their radios

sold

very far

outside of Southern California, so perhaps that explains why there is

precious little information

generally

available regarding this company and its products. Be that as it

may, I will present

what I know and I will

describe for you my own Troy radio. A comprehensive story containing historical, educational, technical and biographical elements & opinions for your entertainment by John Fuhring  Introduction While searching for information on my radio, I couldn't help but wonder why this company had the word 'television' in its name. This is pure speculation, but I am of the opinion that the people behind the Troy Radio and Television Company may have been inspired by the early (1920's) television work done by so many brilliant scientists and engineers, including Philo Farnsworth. I am sure that the engineers at Troy Radio and Television expected television technology to quickly blossom forth just as had other forms of early 20th Century electronic technology, but in fact, television lagged for a long time because suitable camera technology was slow to develop. That, in addition to all the legal fights over patent rights really slowed things down. I also suspect that RCA's Sarnoff, because of perceived threats to his very lucrative system of AM broadcasting networks, threw in a lot of roadblocks, just as he had obstructed the development of Armstrong's FM system. By the mid 1930s, it looked like television technology had matured to the point where there would be a real demand for television sets. Indeed, the 1936 Berlin Olympics were broadcast over TV in Germany, but World War Two and the need to militarize the electronics industry, put an end to commercial television until some years after the war was over. The rise of the commercial market for television products came too late for the Troy Radio and Television Company just as it had for the Farnsworth Radio and Television Company, so in 1941, just as the war began and just nine years after building their first radios, the Troy Radio and Television Company of Los Angeles went out of business. I sometimes wonder if the birth of "The Age of Television" would have occurred five or ten years earlier if it hadn't been for World War Two. Generally we think of warfare as a great stimulator of technological advancement, but I think that it is obvious that both WW 1 and WW 2 actually retarded the advancement of radio and allied technology. It was only later, during the "Cold War," that massive government spending on various "defense" programs resulted in the development of micro-electronic, digital and Internet technologies.  My beautiful Art Deco Model 75 Troy

Radio, circa 1936.

It is my opinion that smaller, AM only radios such as this one, were designed for and bought by people who wanted a nice looking and nice sounding radio for a small apartment or bedroom, but that a radio such as this wouldn't have been an average family's main "parlor" radio. Nevertheless, this is a very high quality radio that sounds good and looks good and for over 50 years it has decorated my bedroom as I am sure it decorated a similar room in its original owner's house. During its short life, the Troy company produced dozens of models of radios including car radios, large console models, relatively small table models and even radio/phonographs. Their products ranged from extremely inexpensive and simple 4-tube Tuned Radio Frequency (TRF) sets for city dwellers, to very elaborate and sophisticated consoles containing many tubes for their wealthy customers. In other words, they built radios for every taste and budget and successfully went head-to-head with big brands like RCA, Zenith, Philco, GE and others - at least in Southern California. Despite their wide range of products and despite their name, they never produced a single television set (that I know of). I think that the key to Troy Radio's success is due to the fact that they began selling their first radios in 1932, just as the worst effects of the Great Depression were being felt and when people were eagerly turning to the radio for affordable entertainment and relief from the worries of the day. Being a local manufacturer, they could save on transportation cost and those middle-man fees that plagued the better known brands and by offering a product of equal quality at a lower price, they experienced almost a decade of success. As were all the radios of this era, the Troy radios were built with each component expertly soldered in by hand and to a design technology that allowed few cost reductions in manufacture. In addition, radios of this era were as much works of art as they were utilitarian and to a greater or lesser degree, they reflected the "Art Deco" styling that was so popular then. A radio had to have grace and style in a pleasing wooden cabinet, or it wouldn't sell. These hand made radios and their cabinets were built to high quality standards with what was then expensive high-tech components so that (by today's standards) these radios were by no means cheap to manufacture. To make matters worse, RCA and Hazeltine held all, and I mean ALL the patents for every single circuit and component in these radios. A license from RCA wasn't easy to obtain nor was it cheap, David Sarnoff made sure of that. It is my estimate that a small radio such as mine would have originally sold for about $20 and in today's money, that would be the equivalent of $400 to $500. In the 1930s, credit cards did not exist, wages per hour were in cents, not dollars and we all know how little money people had to spend in those days. A family or individual would have had to save long and hard to buy one of these radios, but the "Golden Age of Radio" had begun and regardless of their financial condition, everybody had to have a radio. For many Californians, for reasons of price, quality and style, their radio would be one of the Troy models. How I

got my Troy radio a long time ago

This story

is about an actual Troy radio, my radio, a radio that I received as a

present

from my parents about the year 1959. This story is also briefly

autobiographical because it is part of my fun to write about personal

and

historical details than are not usually found in articles of this sort.

The following then is the story of the events that led up to me

being given the radio as a gift.After a long career as a Naval doctor, my dad retired to a little town along the central coast of California and went into private practice. Why my dad chose this Podunk place is a long story and beyond the scope of this essay, but I and my family ended up here for better or worse. Like all doctors, my dad had a "waiting room" where his patients would show up for "appointments" and then be made to wait and wait until he could see them. Maybe that's why doctors call their customers "patients" as a kind of cynical doctor's joke. Yes, people have always had to wait in doctor's offices and for several reasons - because some patients take more time to examine that originally estimated, but mostly because a doctor needs to have a full office and a surplus of patients in case somebody doesn't show up for some reason. Hey, it's a business, businesses need to make money and doctors will tell you that they aren't in it for their health -- that's a "patient's" joke, by the way. So, what did my dad's patient patients do to while away the hours until the he could see them? They did just what they still do today, they read old magazines. To obtain these magazines, my dad's staff took out multiple subscriptions to all the popular journals of the day including Popular Mechanics, Popular Electronics and Popular Science. As their names imply, these were very .. ah.. popular magazines especially with men and boys. You have to realize that this was still a time in America when people built things and manufacturing was thriving. You have to realize that this was still a time in America when inventors and not money managers living extravagant life-styles were popular heroes. In short, we as a Nation had not yet become "cool" and "hip" and many of us were oh-so "square" and (as we say today) "nerds." Being a junior nerd myself and having "The Knack" in its fullest expression, I just loved to get the old magazines from my dad's office when the new issues would arrive to replace them. I loved to read the articles and, what is more, many times I'd build the projects featured in the articles. These magazines were my nerd's lifeline that rescued me and offered me temporary refuge from all the "normal" people I was surrounded by all day, every day. Popular Electronics, Popular Science and even Popular Mechanics magazine would, from time to time, have an interesting article about old shortwave radios and how to get them working again. From this I learned that starting in the early 1930s, the country experienced a shortwave craze and in response to that craze, the majority of the larger parlor radios and even many of the table-top models had at least one shortwave band. Well, even at my tender age, I too was caught up in my own shortwave craze and I eagerly sought out an old radio for my very own. In the meantime, several people told me they had old radios that didn't work anymore, so I started a little business and fixed up several old radios with new tubes and capacitors. Oh yes, by this time I really knew my way around an electronics parts store. Being the Dilbert that I am, I talked and talked about these old radios and had everybody, including my parents, enlisted to be on the lookout for one. The problem is, I didn't understand that other people were not necessarily as technically minded as I was and that almost nobody but me was into this sort of thing. I didn't realize that nobody else in my immediate circle of family and friends knew the difference between an old radio with and an old radio without a shortwave band. My mom was somewhat of a "technical" person, but she really did not understand electrical things and of course, as skilled as my dad was with a fine scalpel and other delicate instruments of eye surgery, he really didn't know (or want to know) which end of a hammer or screwdriver to use -- and that's the truth. Now, where was I? Oh yeah, I was telling about having people look for old shortwave radios for me. During the period of the late 1950s there were some 'antique' stores in Arroyo Grande (about 20 miles from here). Of course I use that term "antique" rather loosely because those stores sold mostly 'j-u-n-q-u-e,' and sometimes they sold old radios too. One weekend my mom and dad drove up there just to look around. While up there, they saw and bought an old Troy radio for me. I'm sure my folks remembered listening to similar radios as young people and so they must have thought that this radio was one I would want. When they got home, they presented the radio to me and at first I was absolutely delighted and a little overwhelmed with pleasure at seeing it (you know what they say: "simple minds, simple pleasures"). I peered in back of the set and saw that it was filled with these huge very, very old fashioned looking tubes, so I knew I was going to love the radio. I plugged it in and turned it on expecting to hear nothing but a loud hum, but to my surprise, the radio came to life after a short warm-up. The radio played beautifully --- on AM -- on AM ONLY. Oh no!! My parents had bought me a useless AM radio that did not have a shortwave band. I was dreadfully disappointed, but considered it extremely ungrateful and ungracious to let my disappointment show, so I kept up my enthusiasm out of a sense of appreciation for what my parents had tried to do for me. In the weeks that followed, it was apparent that the Troy radio wasn't what I wanted, but at least I had a nice decoration for a shelf in my bedroom. It was shortly after this I found a Philco Baby Grand radio in a trash can and it had a shortwave band. That radio became my pride and joy until I realized that the one shortwave band it had was kind of useless too because it didn't go above the 80 meter band. A year or so of pining for a "real" shortwave radio finally resolved itself when my parents bought me a Hallicrafters S-120 radio and, if you are interested, I have written the story of it here on my website. What my

Troy Radio is and is not

Before I

put the radio on its shelf for its long wait and while I was

still experimenting with it, I made some

guesses regarding its technology and guesses regarding how old it was.

Those guesses turned out

to be

quite incorrect, but I held them as "fact" for over 50 years.

So, how did I come to make such incorrect guesses? Well, thanks to the articles I had read in all those magazines, I knew that really early radios operated not on the 'superheterodyne' principle, but on the older 'tuned radio frequency' (TRF) principle. I also knew that many of the TRF radios had a "regeneration" control which made them perform as well as a more complex superheterodyne, but also made them squeal. As a TRF radio should, my radio squealed when I rotated (what I later found out was) the tone control and my mom even commented that she remembered how early radios used to squeal like that. Further proof that I had a TRF radio was the fact that, in my young life, I had never seen tubes that looked so big, looked so odd shaped or tubes that were so densely packed together or had such old fashioned pin type bases. The final proof was my mistaken belief that there was only three tubes besides a rectifier tube. I knew that you can not have a superheterodyne radio with so few tubes and therefore with all this circumstantial evidence, I concluded that I must have a really old, old TRF radio. Now, if I would have taken the trouble and removed the chassis from the wooden case, I would have spotted the mixer tube buried in front and I would have known it was a superheterodyne, but the radio worked so well, there was no reason to take it apart. Rear view of my radio.

I had no idea there was another tube up front, so I thought I had a TRF radio. There is nothing on the chassis or case identifying the model number, so I was at a loss to tell just what model I had. My Troy goes on the shelf for 52 years My Troy was

built just for the AM band. It was without shortwave and

therefore, to me, it was kind of useless, but it was nice looking and

that art-deco dial with the stylized picture of the Trojan Warrior and

the two "Spirit of Saint Louis" style airplanes near the bottom

of the golden dial really appealed to me as being very pretty. If

nothing else, the radio made a nice decoration for my bedroom, so I put

it on a shelf below my window and there it has graced that room for

52 years until just yesterday (December 20, 2011). I left home

after high school, I served in the military during the Vietnam War, I

attended university and lived in Nevada many years, but bought the

family house after my parents died so that when I returned to my old

room as an adult, the radio was still there in the very same place.

From that time until just yesterday, the radio has remained in

its

old place.

Yesterday I removed the radio and then, for the first time, I took the chassis out of its wooden case so that I could restore it electronically and write up yet another boring story for my website. When I took it out of its case, I was in for a big surprise. As I mentioned, all these years I had been under a mistaken notion that my Troy radio was a very ancient TRF radio, but in actuality, it was a more modern superheterodyne and the really old looking tubes weren't as old as I had thought. I must be really weird because I just love to discover the truth behind things, especially things that I've held as "fact" most of my life when, in fact, I was completely mistaken all those years. I don't know how to describe it, I just have this kind of "OHMYGOD(!!)" feeling that makes me want to laugh at myself. With the chassis out of the

case, I was in for some surprises as I learned

that notions I had held for 50 years and more were mistaken. As I have indicated, I was in for a lot of surprises when I removed the chassis from its case for the very first time. First, it was immediately obvious that my radio was NOT a TRF radio. It had two IF cans (one of which is clearly visible from the rear and which I should noticed as a kid) and it has a fifth tube that could only be the mixer/oscillator tube of a superheterodyne receiver. This tube is buried, out of sight, in front of the huge tubes to the rear and so I never noticed it all those years ago. Oh my goodness (!), all the research I had done regarding the early Troy TRF radios had been based on my long held but erroneous assumptions and was now utterly, utterly moot. I had wasted all that time, even capturing schematics, but the radio wasn't a TRF and because its name-plate is missing, I had no idea which model I had. These radios are so rare, there are only a few Troy Radio pictures anywhere on the Internet and I couldn't find anything that even remotely resembled my radio, so I was at a loss. In desperation, I began to go through all the Ryder Schematics looking for something that resembled my radio's electronic design. Getting

a workable schematic for my radio

In other

stories on my website, I talk about the importance of having a good

schematic to work

to, so I needed to begin a search to find out what model I

have. Before I began my search, I inspected each

tube and learned something about its type and function. The

6A7 is a "pentagrid" mixer/oscillator, the 6D6 is a "variable

transconductance" IF amplifier, the 75 is a "diode-triode"

detector/AVC/audio amplifier, the 80 is a full wave high voltage

rectifier and the 42 is a audio power output amplifier. Knowing

all this enabled me to look at many schematics and identify drawings

that came close to my radio's actual design. After looking at several early Troy Radio schematics, I initially concluded that I had a variation of the model 57. There is a picture of a model 57 on the Internet, but it doesn't look much like mine except the rear is very similar and it uses the same tubes except my audio output tube is a 42, not a 41. Finally, the triode section of my 75 tube is not biased with a voltage divider from the negative side of the power supply as shown in the 57's schematic, but is biased using a really strange looking device that I had never seen before and something I didn't have a clue what it might be or how it worked.

Since the schematic of the model 57 seemed to match my radio so closely (except as noted), I captured it and began to redraw it to match my radio in every detail. Below is the schematic as I've so far developed it.

Finally identifying my radio's actual model number

Knowing what I know now, I have to conclude that my radio isn't nearly as old or primitive as I once thought it was. Armed with this model number, I looked up the schematic of the model 75 and sure enough, everything matches my radio. The trouble is, all the schematic drawings of the model 75 look really terrible. Nothing I could find is nearly as good as the drawing that I have already created from the model 57's modified schematic, so that's the one I'm keeping. The little

mushroom-shaped thingey

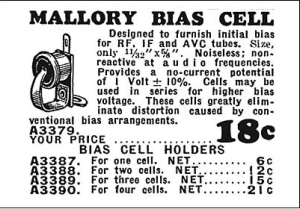

By the

way, the excellent article Mr. Biddison wrote about his own model 75

told me what that

strange mushroom thingey was used for. It is a -1.5 volt cell made by Mallory Battery Company, now known as Duracell, maker of the famous "copper top" battery. It seems that many radios of this age -- and not just the Troy radios, used this little 1.5 volt electrical cell to bias the first audio amplifier. I never would have guessed that anybody would use an electric cell for this because it seems to me to be such a foolish, expensive and complex way to bias the tube. My Fairbanks uses a voltage divider in the negative voltage supply and that is strange enough, but why in the world would anybody use an electric cell that can run down and go dead on you?? What an outlandish idea, but there it was. Later radios simply use a high resistance grid bypass resistor that allows those passing electrons that hit the grid on their way to the anode to make the grid negative and thus "self-biases" the tube. This form of self-biasing works so well and it is so simple, but early tubes like the 75 don't sound so good when using this scheme. The fact is, they sound much better if a fixed negative voltage is used, like from a battery -- or from a voltage divider. Since writing the above, I have found more information on the Mallory Bias Cell. The cell first showed up in radios like mine in 1936 and became very popular and it was anything but an outlandish idea. Since the cells were not required to draw any current, they did indeed last years and years. I even came across a website that claims that they were able to detect measurable voltage out of one that was 50 years old. What really made them practical was the fact that somehow they were cheaper than the resistors and capacitor usually found in more "conventional" kinds of biasing. Wholesale, they only cost about $0.15 whereas even one resistor would cost more. Finally, there is a theoretical advantage to using a highly precision and unchanging voltage for bias, but in all the experimenting I've ever done, it is impossible for me to detect the difference and when you consider that these were AM radios, the difference really is impossible for any mortal person to hear. Personally, I think these little things suck and they are not worth the few extra cents a resistor voltage-divider network would cost, but it is in the nature of manufactures -- following the principles of 'modernity' -- to cut every cent whenever possible -- even if it seems silly.  Something like this would cost about $3

in today's money

To replace the Mallory cell with a watch or hearing aid battery was simply out of the question so I initially put in a 6 megohm resistor and allowed the tube to self-bias as was done with more "modern" radios. This seemed to work great, but I did notice some harshness in the audio after playing the radio for a while. I also noticed that the anode resistor of the 75 tube was getting warm because insufficient bias caused the tube to draw too much current. After experimenting a little, I found that a fixed negative bias of about two volts makes the radio sound its best, so I tapped into the negative voltage where the filter choke coil is taken to ground by a resistor and I put in a simple voltage divider that gives me my negative two volts. How ironic that today resistors are so cheap as to be almost free while a little electric cell to replace the Mallory would be many times more expensive. Anyway, I am so very pleased that I was able to find out what that little mushroom shaped thing is because not knowing what it was very much bugged me. As a precaution, I removed the button cell from its holder, but left the holder in because it provides a convenient place to mount the two resistors that make up the voltage divider I mentioned. The

utter simplicity and genius of tube radios

The

following two photos are of the underside of my radio before and after

I replaced its defective components.

Out of its case, here is the

front of the chassis showing the handsome art-deco dial, the new-looking

When I first looked in back of my radio so long ago

now, I was fooled by how large the tubes were and by their old

fashioned base configuration. Their sockets were very similar to

some of the very oldest tubes dating back to the early 1920s and so I

naturally assumed that they must be very primitive and very simple type

of tubes -- perhaps just one step more advanced than DeForest's Audion

tubes. Well, I was wrong. As large as these tubes were and

as old fashioned as their bases appeared, they were quite advanced

tubes

for their day. speaker, the mixer tube and the antenna tuning coil.  Here is a close-up of the beautiful dial. Notice the gold Trojan Warrior, the encircled Trojan Helmet and world globe with the words "TROY quality RADIO" emblazoned across them and at the bottom of the dial, the wonderful Lindberg "Spirit of Saint Louis" style airplanes. To me this is an absolutely classical expression of the "Art Deco" styling so typical of the 1930s. Some radios of this era carried this to an extreme but I believe that my radio expresses this quite tastefully. A brief word about the vacuum tube technology used in my radio The 6A7 is a pentagrid tube that is a younger brother to all the subsequent tubes of its type. Both the 6A7 and the 6D6 are sophisticated "variable transconductance" amplifiers and, in addition, the 6D6 is a pentode that had all the "inter-electrode capacitance" and "secondary emission" problems of earlier tubes solved. The 75 tube is a both a Fleming Valve type AM detector and a "high mu" audio amplifier. Although the 42 power amplifier tube predates the later "beam power tetrodes," it was a very nice and powerful pentode tube that was the result of some very clever tube development that occurred during the decade of the 1920s. All the tubes in my radio had come on the market not too much earlier and so they represented pretty much the "state of the art" in electronic design when my radio was new in 1936. Because these tubes were so sophisticated, designing my radio around them allowed the radio to perform as well or better than the more expensive and prestigious radios that were designed with eight, ten or more of the older type tubes. I am sure that owners of slightly older radios would have been impressed with how small, but fine sounding my Troy was (and is). I am sure the original owners of my radio were delighted with how the radio was able to fill their apartment or bedroom with plenty of high quality sound when they tuned in one of the many stations broadcasting entertainment, sports or music of that era. The

old radio finally plays beautifully for me, but only after smoking up

my room

Well, yesterday afternoon I decided the time had

come to plug in the old radio and see if it still worked after 75

years. I must admit that I have become rather smug about my

"first power after 50 years" rituals. Up until now, I have had

100% success and my old radios have all come to life as soon as

they were turned on. A big part of that success is due to the

detailed inspection of the entire chassis wiring and verifying that all

work was done properly, so it isn't simply pure luck, but careful work.

This time things went very wrong and my smugness suddenly turned

to horror and panic.What can be more horrifying to a Dilbert like me but to have their project start to smoke when first turned on?!? What can smell worse to a Dilbert like me than the stench of burning phenolic?!? Oh god(!!) the radio began to smoke and the room was filled with this horrible stench, so I quickly killed the power. I searched and searched for over-heated components, but couldn't find any. Completely baffled, I had only one recourse --- yes, I must give the radio one more "smoke test." I pulled out the rectifier tube so that the high voltage section wouldn't be damaged by a possible short and turned on the radio and again I got smoke, but before I turned off the radio I noticed a spark of light. I turned off the lights in the room to make any sparks more visible, situated myself close to where I thought I saw the spark come from and gave the radio a third "smoke test." This time I could clearly see that the 80 tube's (the high voltage rectifier's) phenolic socket was arcing and minor burning was taking place. Those electrodes are quite close together in the rectifier's socket and they carry around 700 peak volts between them when the radio is first turned on. Over all these years, the insulation had obviously broken down there and as the phenolic turned into carbon, further breakdown occurred until a path for electricity was created. To fix it, I simply took my small grinding tool and removed all the carbonized material just as a dentist removes the decayed matter in a bad tooth. There was still plenty of good, undamaged phenolic material remaining to hold in the electrodes, so, unlike a tooth, there was no need to fill up the cavity with something that might itself cause future shorting -- it seemed to me that an air gap would be the best insulator under these circumstances, so I didn't bother putting anything in the cavity. After I had everything fixed and the 80 tube back in, I gave the radio a fourth "smoke test" and I am very pleased to say that the old radio came to life after the usual short warm-up and without smoking this time. In fact, the radio sounded wonderful, simply wonderful and much better than I expected a radio with such a small speaker. Perhaps I shouldn't have been so surprised. These old speakers have a thick and a very high quality cone that work as well as they do in large part because of the powerful electromagnet that is built into them. Cheaper speakers that came with later radios had weak permanent magnets that required a lighter and a larger cone for them to sound as good. By the way, this powerful magnet also acts as a filter (choke coil) for the high voltage power supply. These old radios did not have built in loop antennas probably because America's population was much more rural than it is today and most people put up outside antennas (which work much better than loop antennas) anyway. I connected my newly refurbished Troy radio to my outside antenna and was extremely pleased to find that the AM band was literally filled with signals. As crowded as the band was that night, my radio was able to easily tune each station in turn and tune them in without any of them overlapping. For a simple AM radio, this radio tuned sharply, and its audio was just superb. At first the tone control didn't work because I hadn't wired it in. I wanted to experiment with different values of capacitance to find just the right tone and found that a 0.0047 MFD capacitor in the grid circuit of the 42 tube greatly reduces the high pitched noise on weak stations, but still gives the radio a very nice sound. In fact, even on strong stations, the slightly more base sound is very pleasant to listen to. Conclusions

I now have a 75 year old radio that should be

playing beautifully well into its next 75 years, but you know, I

wonder if there will be a AM radio band 75 years hence? I know

there won't be a "me" 75 years from now. Gee, if there was

something else to listen to locally besides all the nutty right-wing

"Hate Talk Radio" or the equally disgusting right-wing "Christian

Radio" - I would be really happy. I sure hope that KGO up in San

Francisco never goes off the air because if it did, nothing good or

worthy would remain to listen to on AM -- in my opinion.

As mentioned at the beginning of this story, the

Troy Radio and Television Company was a small player in the radio

industry of the 1930s and they manufactured relatively few radios

compared to the "big boys" like RCA or Philco. Couple that to the

fact that only a tiny fraction of all the radios built during that era

escaped being thrown away after they became obsolete and it is no

wonder that today a Troy radio is so rare. I consider myself to

be in possession of a radio that may not be a valuable or sought after

collector's item, but one that still stands out from all the more

common brands and one that is inferior to none of them with regard to

beauty,

technology or quality.

THE END OF MY TROY RADIO STORY

(FOR NOW)

Having arrived this far,

obviously you have a superior attention span and reading ability that

far exceeds that of the

Did

you enjoy this article

or did it suck?majority of web users. I highly value the opinion of people such as yourself, so I ask you to briefly tell me: Please visit my guest book and tell me before you leave my website. If you have an antique AM radio and you need something decent to listen to, perhaps you should buy or build your own  Low Power AM transmitter If you liked this story and love old radios, perhaps you'd like to read the story of my beautiful 1936  Fairbanks Morse Radio Recently I found and restored a 1938 Crosley Super 8 radio that was from a posponed repair job 50 years ago  Please go to my Crolsey Radio Story If you are interested in learning a little about how this and other old radios work, you might be interested in  An essay on Armstrong's Superheterodyne Principle I have lots of other stories about my wonderful old tube radios that you might enjoy, so

|